By Coleman Horsley, PE and Nicole Holmes, PE, LEED AP

There are records showing ancient use of concrete by the Greeks, Assyrians, and Egyptians as early as 1400 B.C.; however, the civilization that utilized concrete so fully that it changed the world of construction forever were the Romans, who used it for 800 years until the fall of the Western Empire in 476. Concrete was still used after this, but to a much lesser degree – until the invention of Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) by Joseph Aspdin in 1824. This not only revolutionized how we approach construction, but also magnified the impact we had on our planet in terms of emissions and our contribution to global warming. To this day, the majority of cement that is produced is OPC, which begs the question: isn’t it time to innovate?

The Problem

Concrete is cheap to manufacture, the ingredients are relatively readily available in most of the world, and it is relatively strong, which makes it an ideal choice as a building material. We rely on it so much that it’s the second most widely consumed material in the world; the only material that we consume more of is water – which actually makes up about 10% of the final weight of concrete. One of the largest issues with this material, however, is that concrete production contributes to 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions (measured in CO2).

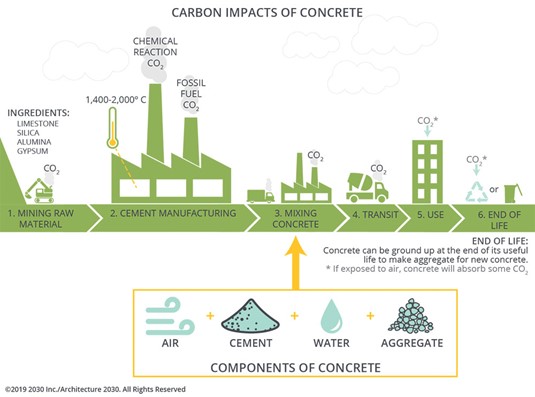

The greatest source of CO2 emissions associated with the production and use of concrete occurs during the manufacturing process. CO2 is released when fossil fuels are combusted to bring the base limestone material up to the reaction temperature to convert it from limestone to cement clinker. CO2 is further released as a result of the chemical reaction itself. While the manufacturing of concrete is responsible for the largest contribution of CO2 emissions, the carbon impacts of concrete are even more significant when considering processes that occur throughout its entire lifecycle, from the extraction of raw materials to manufacturing, transportation, installation, use, and end-of-life. The total greenhouse gas emissions associated with the entire life cycle is often referred to as the whole life carbon, as illustrated below.

The production and use of concrete not only contribute to the overall acceleration of global warming, but also lead to a secondary issue. The increased carbonation of our atmosphere impacts ocean acidification and accelerates the carbonation of concrete due to a faster oxidation reaction with internal metal reinforcement. This causes expansive rust to form, which in turn cracks the concrete. These reactions ultimately lead to concrete needing to be replaced more often, creating additional CO2 emissions and perpetuating the cycle.

What can we do?

Now that we understand how the production and use of concrete contributes to global greenhouse gas emissions, what can we in the AEC industry do to reduce its impact? As a civil engineer focusing on infrastructure projects, we can start with three major ways to reduce CO2 emissions associated with concrete.

First, we can become more efficient with our designs by decreasing the conservative factors that lead to excessive use of materials. This will create more affordable and greener infrastructure. For example, can we reduce the widths and depths of pavements? If we do, it will result in a more economical option for our projects by reducing the carbon impact while also lowering upfront costs.

Second, we can modify the chemistry of our mixes and replace carbon-intensive OPC with either supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) or cement that has been manufactured in a way that decreases its embodied carbon content. These SCMs typically take the form of fly ash, which is a waste product of coal power plants, or ground granulated blast-furnace slag, which is a byproduct of steel production. There are plenty of other low-carbon materials that we can utilize, as well – especially as technologies develop to meet the needs of our ever-evolving industry.

Third, we can re-evaluate outdated specifications and construction practices to create more durable concrete that lasts longer and reduces emissions due to less frequent replacements. For instance, do we really need 4,000 pounds per square inch (PSI) design strength for a sidewalk that does not experience vehicular loading? By lowering the design strength to 3,000 PSI, we can reduce the global warming potential from 262 kg CO2e to 223 kg CO2e, a significant decrease (numbers obtained from the National Ready Mixed Concrete Association [NRMCA]). In New England, we typically allow an abundance of bleed water in the concrete. This can lead to bleed-water getting reintroduced into the top layer of concrete during the finishing process, which thins out the cement content and leads to a much weaker top layer. This in turn can lead to scaling/spalling damage as early as the first winter. Concrete that lasts longer is concrete that we can replace less often. Increasing the life cycle of your pavement is an effective way of lowering your long-term maintenance costs while also lowering your embodied carbon numbers.

What’s Next?

This article serves as a quick introduction to low carbon concrete from a civil engineer’s perspective: however, keep an eye out for future articles that expand upon the different strategies to reduce the carbon impact of our projects providing a deeper study into the available strategies and emerging technologies available.